Writings

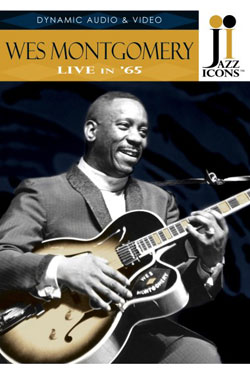

Wes Montgomery Jazz Icons DVD Liner Notes

2007

Wes Montgomery Jazz Icons DVD liner notes by Pat Metheny - 2007

********************************************

Wes Montgomery DVD

By Pat Metheny

In the mere nine years that Wes Montgomery made records under his own name, he established an eternal presence in the music world that can be counted as one of the most enduring testaments to the power of improvisational music.

In the mere nine years that Wes Montgomery made records under his own name, he established an eternal presence in the music world that can be counted as one of the most enduring testaments to the power of improvisational music.

By 1965, when these European television broadcasts were made, Wes was widely regarded as the premier guitarist in jazz. He had recently completed a long stay with Riverside records that had quickly solidified his place as the most important player on the instrument since Charlie Christian.

While Wes continued to be active as a touring musician playing in the kinds of small group settings that mirrored his recorded output to date, a few months before these performances were filmed, Montgomery had recorded the first in a series of records for his new label, Verve (Movin’ Wes), that had him venturing into the new territory of playing in more structured and orchestrated studio situations. Those recordings were the beginnings of his ascent to a level of popular success that had eluded any jazz musician of that era except for Louis Armstrong and Stan Getz.

The year was a time of transition, not just for Wes, but for the world. It is not a coincidence that we can see and feel the spirit of those times in the music Wes made during that year, a year that would later grant him his greatest artistic success followed almost immediately, and possibly ironically, by his first major hit record (Goin’ Out Of My Head).

Beyond his mastery as an instrumentalist, Wes was a carrier of the flame residing in each major player that has illuminated the essential jazz tradition. He was an embodiment of the forward-thinking improvising musician who looked with wisdom and curiosity into the heart of his own moment in time and played a music that commented upon the nature of that cultural moment through the prism that the sophistication of the form at it’s highest level mandates.

As he entered a more produced and arranged sonic environment (the results of which wound up showcasing some of his most lyrical and focused improvisations, critics of that direction and those subsequent Verve and A&M records be damned), his day-to-day life as a gigging musician continued most often in the piano, bass and drums quartet format that suited him well during this period.

The three quartets represented here precede by just a few months what many people regard as the artistic highlight of his career; also a quartet-the aforementioned reference to his classic collaboration with pianist Wynton Kelly, bassist Paul Chambers and drummer Jimmy Cobb. Their masterpiece Smokin’ At The Half Note was recorded in December 1965.

These performances are a most interesting window into the life and playing style of Wes Montgomery. Filmed within a few weeks of each other during the same spring European tour, we are able to witness Wes in action in ways that have largely never been documented.

For all of his acclaim and fame, Wes is woefully underrepresented on film. While the Wes Montgomery we know from his best records, playing with the musicians that he was most associated with appears not to have ever been captured on film, the three shows represented in this DVD release, especially in this newly restored and sonically remastered form, are welcome and insightful additions that provide an incredibly intimate view of Wes in action.

The first segment comes from Holland and features a Dutch rhythm section- pianist Pim Jacobs, his brother, bassist Ruud, and maybe the most consistently important Dutch musician of that era up through today, drummer Han Bennink.

As with the footage from Britan that concludes this DVD, this is Wes playing with musicians that he was most likely totally unfamiliar with, a situation well known to musicians as a playing with a “pick up” rhythm section.

I can attest that this experience can often lead to mixed results. Yet there are some musicians who seem to not only be able to play with anyone, under any conditions, and sound great, but make the others around them play and sound their best too. (Clark Terry would maybe be the ultimate example of this rare and wonderful phenomenon; how many over the years have witnessed him, without saying a word, somehow transform a junior high school big band from somewhere in the rural Midwest into a swing machine by sheer rhythmic persuasion?)

Wes easily fits into this special category. His spirit and presence, not to mention rhythmic authority, drive the music in a masterful way. The minimum required for everyone was to just hang on and go along for the ride, but there are moments along the way that transcend.

You can feel the incredible enthusiasm of the Pim Jacobs Trio at having this amazing encounter with Wes. Early in the first blues, there is a great shot of bassist Ruud Jacobs where the look on his face almost shouts out the feeling of “I can’t believe I am getting to do this!”

Bennink, who has gone on to be one of the most colorful and exciting drummers in jazz over a wildly varied 40+ year career, is already an irresistible presence here and it is easy to see that Wes was getting a kick out of playing with him.

Wes often proved to be a challenge for pianists. While many guitarists stick to single note horn-like playing when soloing with piano, Wes was a player who was constantly dropping in his own polyphonic asides and was ready to launch into full-blown harmonic variations at any point. Pianists used to controlling all the harmonic and rhythm section traffic might prove to be undone by such a challenging force as Wes. Through the quality of his listening, Pim Jacobs brings a level of attention to the details of Wes’s playing here that gives the guitarist the wide berth that he commanded while providing excellent and sensitive accompaniment throughout.

There are many pleasures with this particular footage, including the lush and beautifully recorded sound. Yet the highlight for me is the opportunity to watch Wes in action in between the tunes as a bandleader.

As far as I know, this footage of Wes setting up the tunes and his detailed explanation of “The End of a Love Affair” to the guys, is the most extensive footage of him talking and just hanging out that there is.

What a treat it is to see this side of Wes in action. To a person, every account of Wes’ personality that I have ever heard describes him as being a genuinely warm, funny and energetic man despite his otherworldly skills and talent. (I can personally pay testament to his generosity and goodness from my own brief encounter with him as an awestruck 13-year-old who asked him for his autograph in April 1968 at the Kansas City Jazz festival-he spent some time talking to me and was kind beyond description).

These few minutes in discussion with pianist Jacobs lay to rest one of the mythologies surrounding Wes and the nature of his musicianship. How often in liner notes and articles have we been dutifully reminded of Wes’ supposed inability to read music, the fact that he was “self-taught” and all of the other points of lore trotted out to somehow mystify the genius that is utterly self-evident in the legacy that is his music?

In a particularly illuminating exchange, we see Wes discussing the harmony with pianist Jacobs. In requesting one of his favorite variations on the tune’s descending harmonies we hear a musician not only fluent in the traditional nomenclature of harmony, but one who is thoroughly enlightened, eloquent and direct. (Instead of Bb-7/Eb7/AbMaj7 direct to the following Ab-7/Db7/GbMaj7, Wes requests that an additional II-V anticipating the next change a half step higher be added to set up the next sequence, resulting in Bb-7/Eb7/AbMaj7/A-7/D7/ then onto Ab-7/Db7/GbMaj7 etc.)

It is somewhat of a relief to hear him lay it out in such clear musical vocabulary. It was always apparent in Wes’ music that he had devised one of the most detailed harmonic conceptions ever on the instrument, and as a beginner, when I read album notes and magazine pieces that harped on some kind of almost savant-like description of Wes’ insight into musical invention, I often struggled with trying to imagine how exactly he might have arrived at some of the amazingly ingenious results that infuse his playing without at least occasionally thinking in these kinds of terms (tritone relationships, substitutions, etc.).

Hearing both the rehearsal version at the slower tempo and then the following uptempo version, all of the hallmarks are there of Wes’ genius. As much as we might note the splendorous details of his technique, sound, rhythm and general greatness, I find myself drawn again and again to the quality of melodic material that he was able to generate and sustain. Each idea flows naturally and logically to the next. There is a near-Sonny Rollins level of internal discourse at work, with each idea arriving at a destination, never abandoned along the way.

The general sense of storytelling, the almost inevitable flow that his narrative sensibility provided with such consistency; all of this is on display with an abundance that is difficult to overstate. And doubly so with the apparent effortlessness and grace that seemed intrinsic to Wes; the casual looking around and grinning while improvising at this level would be almost distracting if it wasn’t part and parcel of who he was and the spirit that he was playing from.

In fact, with that smile and ease as he delivers one galvanizing idea after another, it is easy to be reminded that even with his amazing success and popularity, he is still often overlooked as being the major force that is so fully in evidence in the wake of those active nine years.

Short of the signature sound of Miles Davis, and possibly later, bassist Jaco Pastorius, there has been no single instrumental voice that has emerged from the post-1950s era jazz world that has had more general and ongoing sonic impact on the culture at large than the guitar of Wes Montgomery. That sound is everywhere and has been for 40 years plus now. (The fact that Montgomery was willfully excluded from the recent PBS documentary about jazz by director Ken Burns ranks high on the list of that series’ many failings.)

Two days later, on April 4, Wes was joined by the New York rhythm section that would accompany him for the exhaustive series of dates that had preceded and followed on this tour, pianist Harold Mabern, relatively new on the scene from Memphis, bassist Arthur Harper and the great drummer Jimmy Lovelace.

From the first notes of “Impressions,” we see Wes shift to the nature of this entirely different kind of rhythm section. Yet the flow of ideas continues unabated. This quartet had recently played together at the Half Note in New York and could be described as a working band.

Wes’ connection with Lovelace is where the center of the action was in this lineup. Wes always found and cradled the heart of every tempo and then formed a quick allegiance with the drums to make it all happen. With Lovelace, we hear many of the qualities that informed the advances in drumming of that era, all of which suited Wes perfectly.

On “Twisted Blues,” there are some great close ups of Wes’ right-hand thumb technique and the nature of his left-hand playing style. While fretting notes, he only used his first three fingers for his single-note playing but involved his little finger when playing octaves and chords. There is also a totally vertical approach to the geography of the neck at work. He went across strings only when necessary, preferring to go up and down the neck when reaching for ideas and getting the maximum amount of string ringing whenever possible.

“Here’s That Rainy Day” is basically the same arrangement that he would record a month later on his second Verve record Bumpin’. Moved down to the key of E major, this is classic Wes-the rhythmic variation of the melody itself, the little Spanish-sounding rhythm section break that functions as an interlude, and especially the way he transforms what we might loosely call a “bossa nova” into territory that overlaps with the innovations of Horace Silver’s work in this same general area of duple rhythms, transforming the looseness of jazz phrasing superimposed over the steady even eighth-note feeling that was gradually becoming more dominant around this time in a global sense. The world was shifting into a more even eighth-note rhythmic environment by the week.

That Wes was able to tap into that general feeling and serve it up in such a timeless way is central to understanding the meaning of his contribution to jazz.

The quartet moves on to the fastest tempo of the set, “Jingles,” an early favorite from one of his first albums with the great organist Melvin Rhyme. This classic Wes composition is built around the feeling of a long-form modal blues with a bridge in the middle, making an AABA form.

Wes’s chord solo in the center of this take poses challenges for the rhythm section. It is hard to imagine how off the grid this way of playing the guitar must have been for that time. Stylistically, no one had ever really played like that before, so there was no real precedent for how to accompany it other than Wes’ own records. Yet, Wes’ playing had the power and force of a great saxophone player and demanded that kind of energy and was tending towards an almost Coltrane-like momentum.

This set ends with a very pretty version of “The Boy Next Door” (or in this case “The Girl Next Door”) that showcases the unique and beautiful way that Wes could say so much just through his interpretation of a melody. This quality of communication is another essential key to what makes Wes’ endowment to us all so important.

The final show represented here is also the most rare, taking place about a month later (May 5) in Britain during an extended month-long engagement that Wes played at Ronnie Scott’s, London’s most famous jazz club. This was again a pick-up rhythm section consisting of well-known British pianist Stan Tracey, young bassist Rick Laird (who a few years later would become the bassist for the Mahavishnu Orchestra) and drummer Jackie Cougan (who appears to be a sub sent in for this show. The regular drummer on the club engagement was Ronnie Stephenson).

Maybe it is worth noting a few things. This would have been relatively early in the engagement and this quartet was just getting used to playing together. By this time, Wes would have been in Europe and away from home for more than six weeks. For whatever reasons, this show is noticably more restrained compared to the looseness that pervades the earlier two. At times, Wes seems slightly and understandably uncomfortable with the presentation as club owner and saxophonist Ronnie Scott talks about Wes almost in the third person while Wes is sitting just a few feet away.

The highlights in fact are the intro and outro to the show where Wes plays a beautiful unaccompanied version of his “West Coast Blues.” On the outro, we are given the same fantastic, over the shoulder, almost “players” point-of-view shot of Wes’ thumb that occurs occasionally throughout this program. Every detail of his thumb technique is revealed, including the several backstrokes on the fast triplet phrase in the melody mixed in with the more prominent downstrokes that he was famous for. For these moments alone, this footage is priceless.

Wes Montgomery did things with the instrument that fully and finally brought it to the forefront of jazz, a place that it has comfortably inhabited ever since. But for me, as important as Wes’ contributions were as a guitar player, it is the content of his ideas that demand his inclusion in the small pantheon of major players that have ultimately defined this music at its highest level.

Wes’ music always sounded great. This was a blessing and a curse to him in terms of critical perception; it sounded great to anyone, jazz fan or jazz novice. At the time, it is clear that there was already an understood aura of greatness around him. However, there is a notable quality that each Wes recording seems to retain-they just seem to be getting better as the years go by.

The reasons for this are many. There are so many glories to talk about in Wes’ playing. But my feeling is that as much as everyone talks about his penchant for playing phrases in octaves, using polyphony in his improvisations and the whole thing with the thumb, too little is said about the details of his phrasing or the amazing vocal quality that he could invoke at will. Not to mention the amazing quality of melodic development that seems to inhabit virtually every solo he ever played. That sense of finalizing ideas is so embedded in his art as to be almost unnoticeable as that rarest of gifts, which even the best players possess in small doses.

And yet, on an even higher plane, Wes could speak to anyone and everyone on all these different fronts, and more. My interest in him allows me to find these pieces that are of special importance and concern to me as a fan and as a player. There are no doubt thousands of other folks whose relationship to Wes’ music evokes an infinity of emotions and feelings that describe conditions far beyond my grasp that Wes himself might have recognized in ways unimaginable.

At that point, what we are talking about is that source in the pinnacle position-soul.

Above and beyond any description of the means, the result dripped with that sweetest kind of humanity. From Wes Montgomery-the greatest guitarist of all time.